Today in 1865 Abraham Lincoln went to Ford’s Theater in Washington, and, as we all know, it didn’t go well.

And yet, five years later, he appeared in a portrait of his widow, Mary Todd Lincoln, putting his hands on her shoulders.

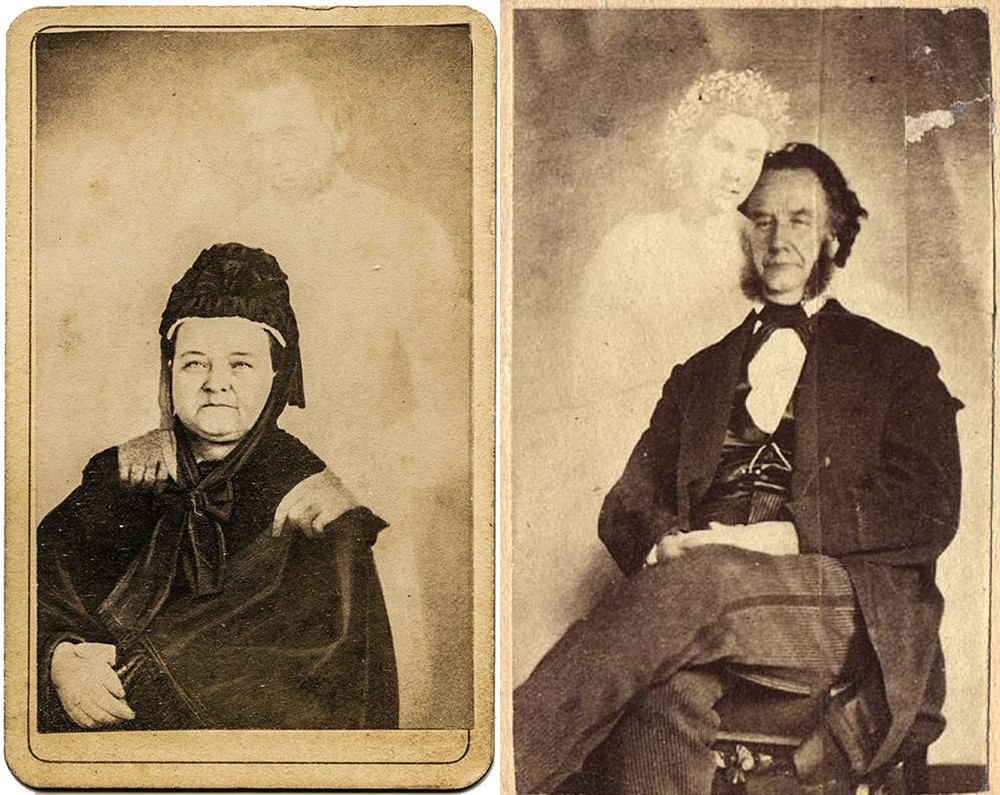

It was the work of a so-called “spirit photographer” known as William Mumler.

Today it’s pretty widely accepted that Mumler’s works were not actually the souls of the departed showing up for portraits.

But this much is true: in the 19th century, many people wanted to believe it.

This was in the time after the Civil War.

Hundreds of thousands of families had lost loved ones, and anyone who promised a way to reunite with them had an audience.

This is when seances were very popular, for example.

Spiritualism was a growing movement.

Mumler, who was experimenting in the new world of photography, was taking a self-portrait one day.

But when the print was finished, there was another figure in there, what he claimed was a young woman “made of light.”

A friend who was involved in the Spiritualist movement figured there must have been a spirit in the room when he took the selfie.

So Mumler started promoting himself as a spirit photographer.

At a time when a portrait would often cost a dollar, he charged ten, because his portraits would include images of the dearly departed.

Well, sometimes they would.

Mumler said he couldn’t guarantee that anyone would show up, or that they would be the loved ones the customers wanted to see, or if it was them, that they would look the way they looked when they were alive.

One woman sat for a portrait and Mumler said the spirit that appeared in her image was her late brother, except that the brother later came home from the Civil War, very much alive.

In 1869, the authorities arrested Mumler for fraud and put him on trial.

By then there were plenty of photographers and others who were convinced Mumler was just using old negatives to construct the so-called “spirit photographs.”

P.T. Barnum, the showman of showmen, proved that the images could be faked, by creating a picture of himself with Abe Lincoln.

But the defense said no one had shown evidence that Mumler faked the photos, or that the photos in question were actually fakes at all.

In fact, experts still aren’t sure how Mumler’s images were made.

So he was acquitted.

And while he mostly gave up on spirit photography, he didn’t give up on the camera.

His next famous creation was something called the Mumler process, and this one was genuinely useful.

It made it easier for photographs to be reproduced on newsprint.

As Smithsonian magazine once noted, a guy who made a business out of likely fake images is somehow also the guy who made it possible for photos to become a huge part of the news business.

Today in 1912 is when the Titanic hit an iceberg.

One of those on board was Richard Norris Williams II.

He spent a great deal of time waist-deep in the freezing Atlantic water; after he was rescued, doctors wanted to amputate both his legs.

He said no, and not only did he recover, he went on to become a men’s doubles champion at Wimbledon and an Olympic gold medalist.

When a 19th-Century ‘Spirit Photographer’ Claimed to Capture Ghosts Through His Lens (History.com)

The Titanic survivor who won Olympic gold at Paris 1924 (Olympics.com)

Our Patreon backers add all the spirit into this show

Photos via Wikicommons