The national holiday known as Martin Luther King Jr. Day. is marked on the third Monday in January, plus today is the actual day in 1929 that Dr. King was born in Atlanta, Georgia.

That’s the city where Dr. King learned that he’d won the Nobel Peace Prize, and the city that gave him a warm welcome for the honor, though putting that warm welcome together got complicated.

It was October 14, 1964 that Coretta Scott King called her husband, Martin Luther King, Jr., to let him know that, at just age 35, he’d won the Nobel Peace Prize.

He’d been nominated by the American Friends Service Committee, and the chair of the Nobel committee said that Dr. King was “the first person in the Western world to have shown us that a struggle can be waged without violence.”

He left for Europe in early December.

First he traveled to London, where he visited St. Paul’s Cathedral and met with peace groups in the UK.

Then, at the awards ceremony in Oslo, Norway, he said that the award meant the world was having “a profound recognition that nonviolence is the answer to the crucial political and moral question of our time.”

He shared the Nobel prize money with a number of civil rights groups.

It was a global honor for someone who was probably the most famous citizen of Atlanta, Georgia in the world.

But back home, Dr. King was getting a much cooler reception.

A group of prominent local officials had been trying to organize a dinner in King’s honor, but they were getting some quiet and strong pushback.

Dr. King was a Black civil rights leader in a largely segregated city.

Some business leaders may have opposed the civil rights movement, while others were irritated that King had been speaking up during local labor protests.

There were reports of a whisper campaign to keep white business owners from buying tickets to a dinner in Dr. King’s honor.

The newspapers started to report on these challenges, and the most powerful people in Atlanta started realizing what it would do to their city’s reputation if it held a dinner for Dr. King with a lot of empty seats.

So the city’s top business leaders gathered for a meeting with two very big names.

First, Atlanta’s mayor, Ivan Allen told the business owners that he would take note of who decided not to show up for the dinner.

Then, J. Paul Austin, the head of Atlanta’s biggest company, Coca-Cola, explained that he led a global company and that “it is embarrassing for Coca-Cola to be located in a city that refuses to honor its Nobel Prize winner.”

According to eyewitness reports, Austin didn’t stop there.

He said “The Coca-Cola Company does not need Atlanta. You all need to decide whether Atlanta needs the Coca-Cola Company.”

Just two hours after that meeting, the results of that decision were in: every single ticket for the dinner had been sold.

And so, on January 27, 1965, Black and white residents of Atlanta came together in public to share a meal in honor of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., winner of the Nobel Peace Prize.

How Martin Luther King Jr.’s 1964 Nobel Peace Prize challenged Atlanta’s tolerance (Atlanta Journal-Constitution)

Nobel Peace Prize (The Martin Luther King Jr. Research and Education Institute, Stanford University)

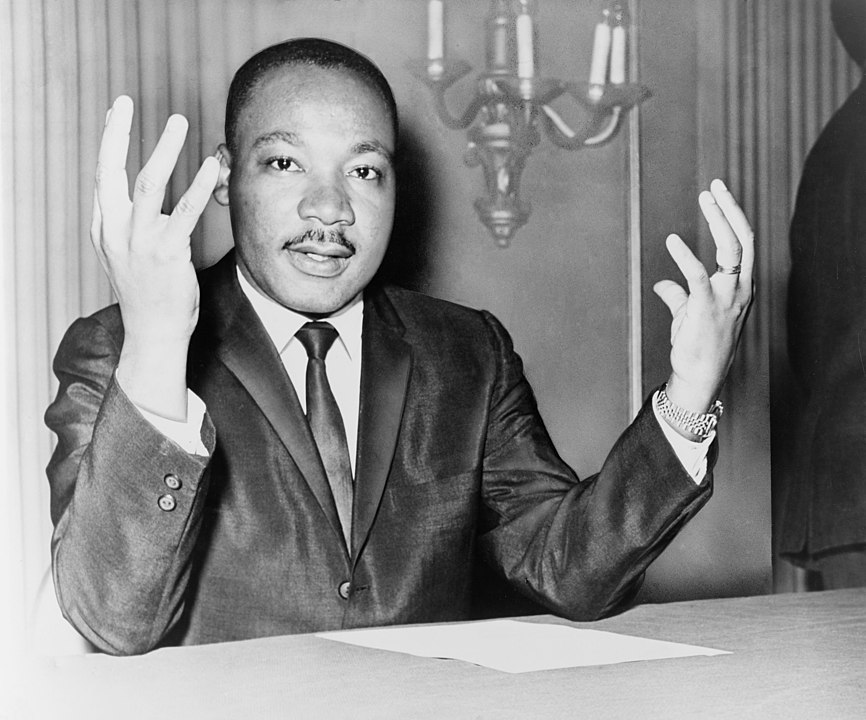

World Telegram & Sun photo by Dick DeMarsico, via Wikicommons