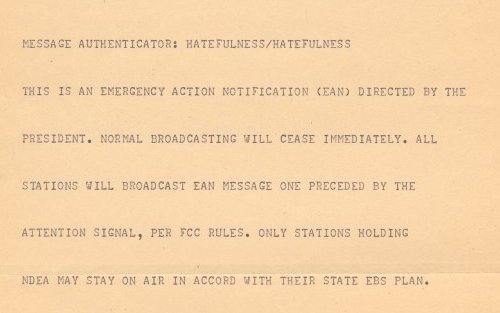

What’s that line in the Maya Angelou poem? “You may shoot me with your words, You may cut me with your eyes, You may kill me with your hatefulness, But still, like air, I’ll rise.” Hatefulness – or, at least, the word “hatefulness” – didn’t kill anyone during the great False National Emergency of February 20, 1971, but it sure did scare the crap out of people in Fort Wayne, Indiana.

“Hatefulness” was the daily code word for the Emergency Broadcast System, set up in the wake of the Cuban Missile Crisis so authorities could get information out fast during a national emergency. Each day EBS would send out a message to participating TV and radio stations via teletypes and wire machines indicating that everything was either kosher or life as we knew it was about to be obliterated in an atomic firestorm. The broadcasters could tell even-steven from eve of destruction by checking the EBS wire’s authentication message against a set of codes sent out at the start of each month.If the messages matched, broadcasters were to stop normal operations and go into a kind of standby mode until authorities sent further instructions, like “stand by for a message from the president,” or “proceed to your local civil defense shelter,” or “you guys remember that Country Joe and the Fish song? Well, they’re right – there ain’t no time to wonder why/whoopee, we’re all gonna die.”

The authentication code for February 20th, 1971 was “hatefulness” – kind of a creepy word choice, given its purpose – and that was the word at the top of the morning EBS message.

Teletypes printed messages at the ultra-fast rate of about 6 characters a second, so you can imagine what it must have been like to get this message, to match up the authentication codes and then to follow along as the wire spelled out… slowly… exactly how little time you had left on earth.

Still, there was a job to do, and dutiful broadcasters like this fellow at WOWO-AM in Fort Wayne, Indiana, took to the airwaves to warn Americans that the government had declared a national emergency and it was unlikely that anyone in the the Fort Wayne area would be alive to hear the end of the Partridge Family’s hit “Doesn’t Somebody Want to Be Wanted?”

This broadcast and other reports about the day’s events illustrates just how much could go wrong under the EBS procedures of the day, starting with EBS control inadvertently sending out the “end times” message and subsequently freaking out Fort Wayne’s AM radio listeners, who responded by flooding the station with calls to find out what the heck was going on. Actually, relatively few stations actually broke into their programming at all- a lot of stations had no idea what to do with the message, and many of those that did know what to do dismissed the alert as a mistake. The civil defense people quickly sent out another message canceling the alert (authentication code: “impish” – no one was laughing, though) and later began retooling the EBS alert process from scratch, doing away with the code words and, probably, the dude who sent out the false alarm. Fort Wayne returned to normal, though it’s said local clothing merchants had a lot of new customers on February 21st, owing to all the soiled pants.

One final note: one of the primary functions of EBS was to give the president quick access to the nation’s entire broadcast system, so he could speak to the whole country at once. But as the government started wising up to the power of mass media, they realized even the Commander in Chief might not be the most reassuring voice during a nuclear crisis. Who was, you ask? Entertainment impresario Arthur Godfrey, of course! The feds had Godfrey record a message along the lines of “yes, the country is being nuked, but try not to panic.” Researchers have confirmed there was such a message, though they haven’t yet found a copy. Still, it’s good to know that midnight on the Doomsday Clock just means it’s Arthur Godfrey Time.