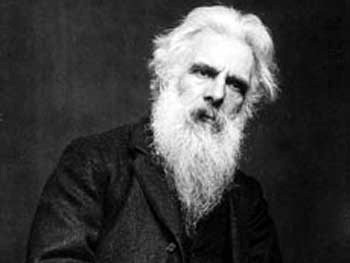

If you heard a recent episode of Cool Weird Awesome, you heard the story of how photographer Eadweard Muybridge rigged up a series of cameras to capture the movement of a galloping horse.

It was essentially the birth of motion pictures.

It took years to put that system together and make it work, though it wouldn’t have taken nearly as long if Muybridge hadn’t been put on trial for murder (!)

Muybridge may have always been an odd duck, but he suffered a head injury in a stagecoach crash in the 1860s and after that he was more than just a little odd.

One researcher said he was known for taking risks as well as “emotional explosions.”

In 1872 the photographer married Flora Stone, and several years later he gave birth to their son, Floredo Helios Muybridge.

Only Muybridge thought maybe the child wasn’t his son after all.

He did spend a lot of time away from home on photography trips, after all.

And then he found a series of letters his wife had exchanged with their friend Harry Larkyns, which included a picture of the youngster labeled “Little Harry.”

You could probably classify Muybridge’s reaction as one of his emotional outbursts.

Or as a lot more: Muybridge followed Larkyns to Calistoga, California, where he was working at the time, met him at the door of a hotel.

A witness said Muybridge said “I have brought you a message from my wife,” and then fatally shot Larkyns at point blank range.

Then he surrendered himself to the authorities.

At trial Muybridge offered two defenses at once.

He pleaded insanity, and there was testimony about how he had never been the same since that stagecoach crash.

But Muybridge’s lawyers also argued the killing was justified because Larkyns was a lustful man, a seducer of virtuous women and he had to be stopped to protect Mrs. Muybridge.

The judge told the jury flat out that the law didn’t allow men to kill other men over alleged adultery, but the jury acquitted the defendant anyway.

Reportedly their only argument was whether to say he was not guilty by reason of insanity or just plain not guilty.

And that was it, except for a few newspapers that suggested that the real culprit in all of this was the wife, since it takes two people to have an affair!?!

She ended up divorcing Muybridge, but only lived for five more months.

The baby ended up at an orphanage.

As for Muybridge, his career took off after the trial; he first went to Central America for a photo project, then returned to the US to return to his work for wealthy industrialist Leland Stanford, who wanted to know whether a horse’s four limbs were all off the ground at the same time while it ran.

Finally, in June 1878, Muybridge took the series of photos for which he is most famous, images of a running mare named Sallie Gardner in motion.

He was a pioneer in what was known as chronophotography, sequential images that depicted movement and paved the way for video.

Though I have to hope he didn’t refer to his photo assignments as “shoots.”

There’s a grave marker in Salt Lake City, Utah that reads “Lilly E. Gray, June 6, 1881 – Nov. 14, 1958 – Victim of the Beast 666.”

She actually died of natural causes, but her husband Elmer claimed they had been persecuted by the government, which apparently he referred to as the “Beast 666.”

We don’t know whether Mrs. Gray agreed or not, but we do know she was buried as far apart from her husband as possible in the cemetery.

Did Eadweard J. Muybridge get away with murder? (Christian Science Monitor)

Muybridge in Motion: Travels in Art, Psychology and Neurology (Arthur P. Shimamura)

The mystery of Lilly Gray ‘victim of the beast’ unearthed (Fox 13 Now)

Do a good deed for a show about bad deeds, back us on Patreon

Image via Wikicommons