Springfield was home to Abraham Lincoln in life and is home to his body in death, but when the president died in 1865 it wasn’t certain that he would return to Illinois’ capital city for burial. Certainly the townspeople wanted him back – as soon as news of his death hit the papers, prominent Springfielders started making elaborate plans to make the whole of downtown a shrine to the fallen president. But that got on the nerves of Mary Lincoln, who never got along with the Springfield set and found their plans so presumptuous she almost sent her husband elsewhere. As James Swanson describes in his book Bloody Crimes: The Chase for Jefferson Davis and the Death Pageant for Lincoln’s Corpse, Mrs. Lincoln kept them hanging – “perhaps, she hinted, [the burial place] might be Washington. Or perhaps Chicago. Or maybe somewhere else.” It wasn’t until Secretary of War Edwin Stanton came to Mary Lincoln and reminded her that he had to send the funeral train somewhere that she finally settled on Springfield.

Stanton’s great inspiration was to send the funeral procession along roughly the same train route as Lincoln took on his way to Washington after being elected; where local dignitaries had shaken hands with, and heard speeches by, their president-elect, they would now view his remains and pay their respects. After several weeks, ten public funerals and over a million mourners lining up at all hours of the day and night to say goodbye to the president, the funeral train reached Springfield on the morning of May 3, 1865, with thousands of Springfielders on hand. The honor guard brought Lincoln’s casket several blocks down the street to the State House, where he lay in state for a full 24 hours, with 75,000 mourners filing in to see him. After that, it was off to Oak Ridge Cemetery for burial.

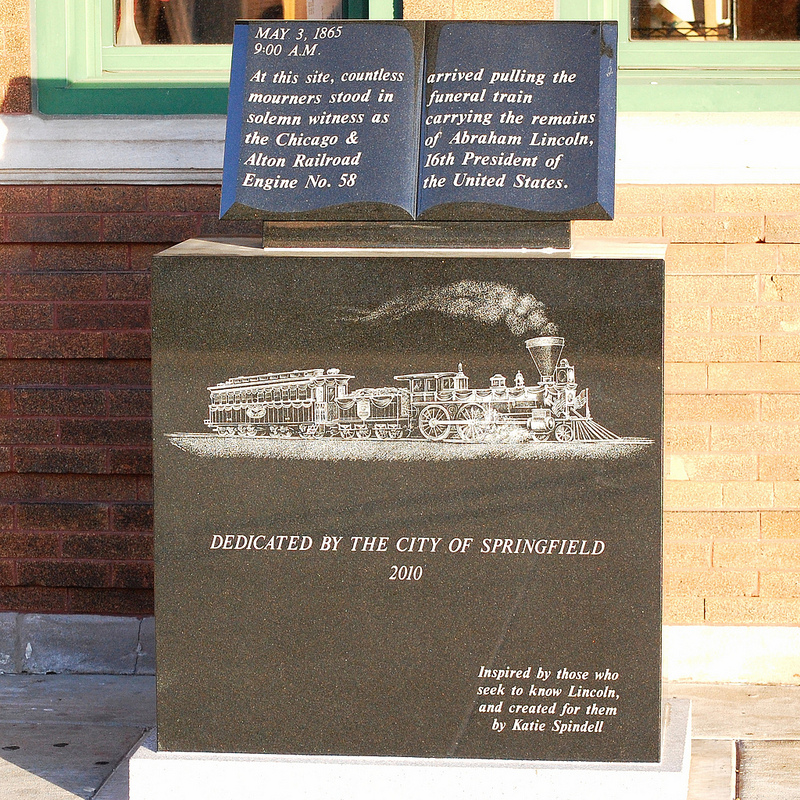

Lincoln’s 200th birthday in 2009 redoubled Illinois’ efforts to map the Great Emancipator’s path through the state; Springfield resident Katie Spindell had one suggestion. Spindell had worked for years answering tourists’ Lincoln questions at the downtown visitors center, and she pushed for a marker at the train station; even though the building that was on the site in 1865 had long since been replaced, she said, people still wanted to see the spot. With $8,000 in funding from city tax credits, she designed a simple, elegant black stone monument that marks the final stop on the biggest funeral procession the country had – and probably has – ever seen.